A few years ago I interviewed 15 local men and women about their first-hand experiences in the military during World War II. Recently I’ve been watching Ken Burns’ magnificent documentary, “The War,” on PBS and am again struck by the tale of how this country coped during that unique period of history.

I’ve gleaned new information from the Burns piece. For instance I had wondered as a youngster, why we were always collecting things for the war effort: newspapers, scrap metal, tin foil, even string. According to the film, part of the reason was to deliberately include those at home in the hardships of war. It certainly worked; I can remember feeling patriotic as could be doing without cake on my birthday because there was no sugar. In school we purchased saving stamps for 10 cents or a quarter. These would be pasted into little booklets that, when full, would buy U.S. War Bonds.

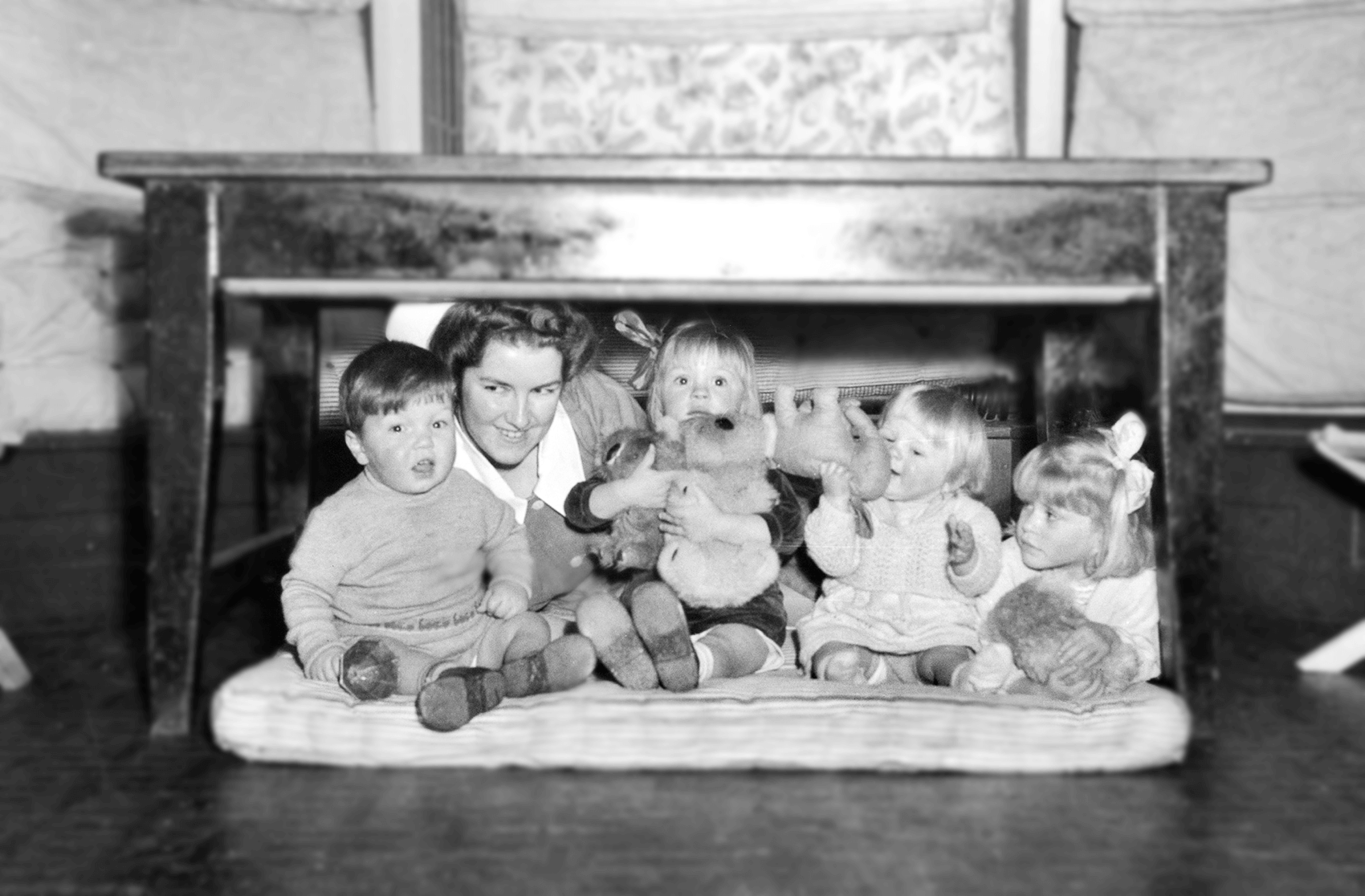

There were few dads or older brothers around. Under my mother’s strict orders we wrote to our father every single day. A lot of “How are you. I am fine. I love you” made it in to mail calls far away. It was thrilling to get letters back with portions blacked out. That meant the original letter had contained sensitive material that we must not know about. We felt like spies.

I had real fears during those days. Aside from the worries over family and friends actually in uniform, I can remember feeling that we would surely be attacked. There were rumors (millions of them) that the Germans were in submarines parked up and down the East Coast, ready to come ashore and herd us all into prison camps. Anyone with an accent of any kind was highly suspicious.

When we walked to school, being careful to step on every crack in order to break Hitler’s back, we bellowed at the top of our young lungs, “Whistle while you work, Hitler is a jerk, Mussolini is a meany, Tojo’s out of work.” On the school swings we sang, “Comin’ in on a Wing and a Prayer, Look Below there’s a Field over there.” The War was everywhere.

We had air raid drills. If you owned a car and were lucky enough to get some gas for it, you were to put tape over the top half of your headlights so as not to allow them to be seen by enemy aircraft. And when the fire siren went off with a particular wailing sound, we were to get into our houses and turn off all the lights…that’s all the lights. Our family got a good scolding from the air raid warden, a local official who wore a white metal helmet, when he spotted our cellar light on during a drill.

I had my own terrors. My older brother would have me paralyzed with fear while he counted the imaginary German planes flying over. He had me in such a state, I could hear the drone of the engines and screech of the bombs as they headed for us, ready to take out the whole town, all because of one cellar light.